import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltLecture 5 - Visualization

Overview

We provide general principles for visualization and cover the basics of plotting in python with Seaborn and Matplotlib.

References

This lecture contains material from:

- Seaborn documentation

- Chapter 4, Data Science: A First Introduction with Python (Timbers et al. 2022)

- Chapter 9 Python for Data Analysis, 3E (Wes McKinney, 2022)

- STAT545, UBC

- Leek, J. and Peng, R. What is the question? Science, 347(6228):1314–1315, 2015.

- Gelman, A., Pasarica, C. and Dodhia R. 2002. “Let’s Practice What We Preach: Turning Tables into Graphs.” The American Statistician 56 (2).

Introduction

Asking questions about data

A visualization helps answer a question about a dataset.

A good visualization will clearly answer your question without distraction; a great visualization can illustrate what the question was without any text explanation.

Types of questions (Leek and Peng, 2015)

From Data Science: A First Introduction with Python:

- Descriptive: a question that asks about summaries of a dataset without interpretation

- Exploratory: a question that asks if there are patterns or trends in a single dataset (often used to develop hypotheses)

- Predictive: a question that asks about predicting measurements for individuals

- Inferential: a question that looks for patterns or trends and tests for applicability in a wider population

- Causal: a question that asks whether changing one variable will lead to a change in another variable, on average in a population

- Mechanistic: a quesetion that asks about the underlying mechanism

Generally we use visualization to help answer descriptive and exploratory questions.

Examples of exploratory questions:

- What is the data quality? Are there inconsistencies or illogical values?

- What are the distributions of variables?

- What associations do there seem to be between variables?

From Gelman et al. (2002): visualizations are most helpful to:

- facilitate comparisons

- reveal trends

A famous graph

John Snow’s cholera map (1855):

Cholera is an intestinal disease that can cause death within hours of onset of vomiting

In 1854, there was a cholera epidemic in Soho, London

John Snow, an obstetrician, believed that contaminated water wells were the source of the epidemic

This is the famous map he created which showed cholera cases (black rectangles) clustered around the well at intersection of Broad and Cambridge Streets.

Source: wikipedia

Visualization principles

Convey the message

- make sure visualization answers the question as simply and plainly as possible

- use legends and labels so visualization is understandable without reading surrounding text

- ensure data is clearly visable

- use color schemes understandable by those with color blindness

- choose scale appropriately (e.g. log scale)

Minimize noise

- avoid chartjunk! e.g. distracting grid lines, gratuitous use of icons, unnecessary 3D

- use colors sparingly - too many colors can be distracting

- if your plot has too many dots or lines and starts to look messy, you need to do something different!

- don’t adjust axes to zoom in on small differences. If the difference is small, show that it is small!

Figure 24.1: From Data Looks Better Naked by Darkhorse Analytics

No no’s

- No pie charts!! (They encode quantitative information in angles and areas, which are hard to judge)

- No stacked bar charts!

Examples of misleading graphs.

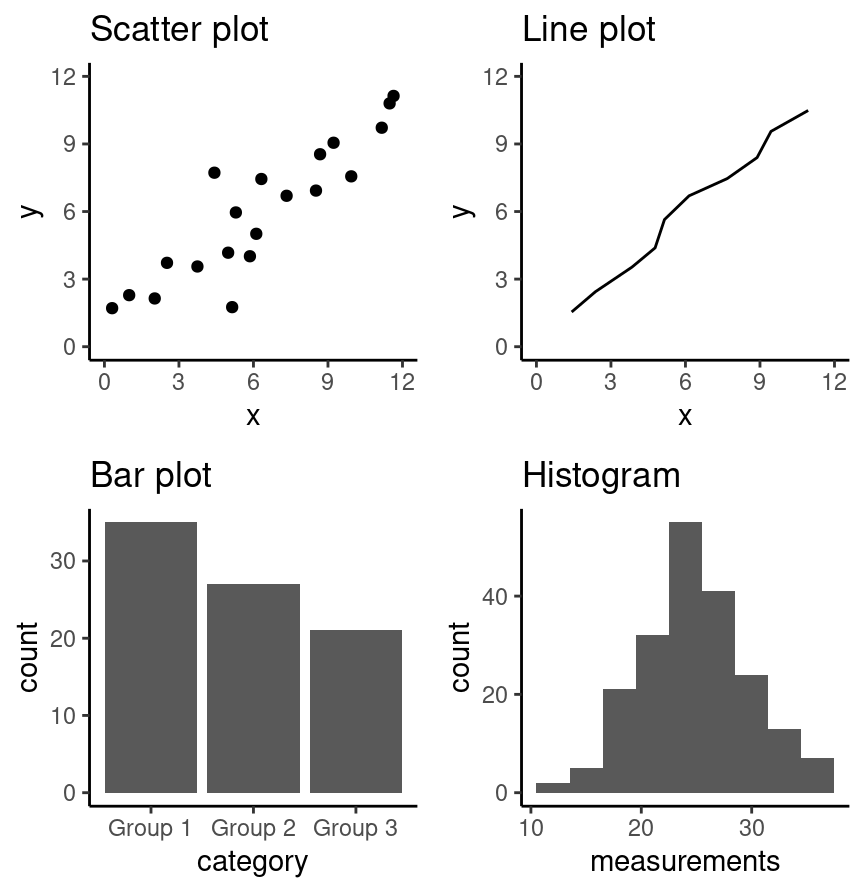

Choice of visualization

Summary of basic visualizations (from Data Science: A First Introduction with Python)

- scatter plots visualize the relationship between two quantitative variables

- line plots visualize trends with respect to an independent, ordered quantity (e.g., time)

- bar plots visualize comparisons of amounts

- histograms visualize the distribution of one quantitative variable (i.e., all its possible values and how often they occur)

Import packages

Let’s now import some packages.

We will also use statsmodels (install this package in your msds597 environment).

import statsmodelsSeaborn Relplot

The sns.relplot() function visualizes statistical relationships using either scatter plots or line plots.

The default is a scatter plot. For line plots, use the argument kind='line'.

Let’s first look at the tips data, available in Seaborn.

tips = sns.load_dataset("tips")

tips.head()| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 |

g = sns.relplot(data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip")

g.figure.set_size_inches(5, 3)

sns.relplot(data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip",

hue="time",

aspect=1.5,

height=3.5)

sns.relplot(

data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip",

hue="smoker",

style="time",

aspect=1.5,

height=3.5

)

sns.relplot(

data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip",

hue="size",

aspect=1.5,

height=3.5

)

sns.relplot(data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip",

hue='time',

size="size",

aspect=1.5,

height=3.5)

sns.relplot(data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip",

hue='time', # colors

style='day', # markers

size="size", # size of the points

col='sex', # subplots in columns

kind='scatter', # lineplot or scatterplot

row='smoker',

height=2.5,

aspect=1.5) # subplots in the rows

sns.relplot(data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip",

hue='time',

style='sex',

size="size",

aspect=1.5,

height=3.5)

dowjones = sns.load_dataset("dowjones")

dowjones.head()| Date | Price | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1914-12-01 | 55.00 |

| 1 | 1915-01-01 | 56.55 |

| 2 | 1915-02-01 | 56.00 |

| 3 | 1915-03-01 | 58.30 |

| 4 | 1915-04-01 | 66.45 |

sns.relplot(data=dowjones,

x="Date",

y="Price",

kind="line",

height=3,

aspect=3)

fmri = sns.load_dataset("fmri")

fmri.head()| subject | timepoint | event | region | signal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | s13 | 18 | stim | parietal | -0.017552 |

| 1 | s5 | 14 | stim | parietal | -0.080883 |

| 2 | s12 | 18 | stim | parietal | -0.081033 |

| 3 | s11 | 18 | stim | parietal | -0.046134 |

| 4 | s10 | 18 | stim | parietal | -0.037970 |

sns.relplot(data=fmri,

x="timepoint",

y="signal",

kind="line",

aspect=2,

height=3)

sns.relplot(

data=fmri,

kind="line",

x="timepoint",

y="signal",

hue="event",

height=3,

aspect=2

)

sns.relplot(

data=fmri,

kind="line",

x="timepoint",

y="signal",

hue="region",

style="event",

height=3,

aspect=2

)

sns.relplot(

data=fmri, kind="line",

x="timepoint", y="signal", hue="region", style="event",

dashes=False, markers=True,

height=3,

aspect=2

)

sns.relplot(

data=fmri,

kind="line",

x="timepoint",

y="signal",

row="region",

col="event",

height=3,

aspect=1.5

)

sns.relplot(

data=fmri, kind="line",

x="timepoint", y="signal", hue="subject",

col="region", row="event", height=3)

Linear regression

Seaborn also has an lmplot function which plots data and a regression model. Let’s explore this function using the mpg dataset.

This dataset contains a subset of the fuel economy data that the EPA makes available on http://fueleconomy.gov. It contains only models which had a new release every year between 1999 and 2008 - this was used as a proxy for the popularity of the car.

- Format

A data frame with 234 rows and 11 variables:

manufacturer: manufacturer namemodel: model namedispl: engine displacement, in litresyear: year of manufacturecyl: number of cylinderstrans: type of transmissiondrv: the type of drive train, where f = front-wheel drive, r = rear wheel drive, 4 = 4wdcty:city miles per gallonhwy: highway miles per gallonfl: fuel typeclass: “type” of car

mpg = pd.read_csv('../data/mpg.csv')mpg.head()| manufacturer | model | displ | year | cyl | trans | drv | cty | hwy | fl | class | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | audi | a4 | 1.8 | 1999 | 4 | auto(l5) | f | 18 | 29 | p | compact |

| 1 | audi | a4 | 1.8 | 1999 | 4 | manual(m5) | f | 21 | 29 | p | compact |

| 2 | audi | a4 | 2.0 | 2008 | 4 | manual(m6) | f | 20 | 31 | p | compact |

| 3 | audi | a4 | 2.0 | 2008 | 4 | auto(av) | f | 21 | 30 | p | compact |

| 4 | audi | a4 | 2.8 | 1999 | 6 | auto(l5) | f | 16 | 26 | p | compact |

Some questions we may ask:

- do cars with big engines use more fuel than cars with small engines?

g = sns.relplot(mpg, x='displ', y='hwy', hue='class')

g.set_axis_labels('Engine Displacement (L)','Highway miles per gallon')

g = sns.lmplot(mpg, x='displ', y='hwy')

g.set_axis_labels('Engine Displacement (L)','Highway miles per gallon')

g = sns.lmplot(mpg, x='displ', y='hwy', hue='drv')

g.set_axis_labels('Engine Displacement (L)','Highway miles per gallon')

We can also use an order-2 regression model. This computes the regression coefficients for the model:

y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i + \beta_2 x_i^2 + \varepsilon_i

sns.regplot(mpg, x='displ', y='hwy', order=2)

plt.gca().set_xlabel('Engine Displacement (L)')

plt.gca().set_ylabel('Highway miles per gallon')Text(0, 0.5, 'Highway miles per gallon')

We can also use locally weighted scatterplot smoothing.

From statsmodels:

Suppose the input data has N points. The algorithm works by estimating y_i by taking the frac*N closest points to (x_i,y_i) based on their x values and estimating y_i using a weighted linear regression. The weight for (x_j,y_j) is tricube function applied to abs(x_i-x_j).

sns.regplot(mpg, x='displ', y='hwy', lowess=True)

plt.gca().set_xlabel('Engine Displacement (L)')

plt.gca().set_ylabel('Highway miles per gallon')Text(0, 0.5, 'Highway miles per gallon')

Seaborn Displot

Seaborn sns.displot contains functions to visualize the distribution of data.

penguins = sns.load_dataset("penguins")

penguins.head()| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | Male |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | Female |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | Female |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | Female |

Histograms

One of the most common approaches to visualizing a distribution is a histogram.

In a histogram, the x-axis (corresponding to the data variable) is divided into a set of bins and the count of observations falling within each bin is shown using the height of the corresponding bar.

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

We can choose the bin size:

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

binwidth=7.1,

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

Or specify the number of bins we want:

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

bins=20,

height=3,

aspect=1.5

)

sns.displot(penguins, x="flipper_length_mm",

binwidth=0.3,

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

binwidth=30,

height=3,

aspect=1.5) # binwdith too big, the two hills in the data are not visible

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

bins=15,

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

tips = sns.load_dataset("tips")

tips.head()| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 |

sns.displot(tips,

x="size",

discrete=True,

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

sns.displot(tips,

x="day",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

# no need to specify discrete=True beacuse seaborn figures it out on its own

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

hue="species",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

hue="species",

col='island',

height=4)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

hue="species",

multiple="dodge",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

col="sex",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

Kernel density estimation

Rather than using discrete bins, a kernel density estimate plot smooths the observations with a kernel.

\widehat{f}_h(x) = \frac{1}{nh}\sum_{i=1}^n K\left(\frac{x - x_i}{h}\right).

The default is to use a Gaussian kernel: \widehat{f}_h(x) = \frac{1}{nh\sigma}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\sum_{i=1}^n \exp\left(-\frac{(x - x_i)^2}{2h^2\sigma^2}\right)

where \sigma is the standard deviation of the sample \{x_1,\dots, x_n\}.

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

kind="kde",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

kind="kde",

bw_method=0.05,

height=3,

aspect=1.5) # setting the bandwidth

# overfitting

# curve is jittery and the jitter is from noise, bandwidth is too small

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

kind="kde",

bw_method=0.3,

height=3,

aspect=1.5) # setting the bandwidth

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

kind="kde",

bw_method=2,

height=3,

aspect=1.5) # setting the bandwidth

# underfitting:

# bandwidth too big, curve too smoothed out, not informative

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

hue="species",

kind="kde",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

hue="species",

col='island',

kind="kde",

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="flipper_length_mm",

hue="species",

kind="kde",

fill=True,

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

Bivariate distributions

# bivariate histogram

sns.displot(penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

height=4)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

cbar=True,

height=3,

aspect=1.25) # adding a colorbar

sns.displot(penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

hue='species',

kind='hist',

height=3) # default is hist

sns.displot(penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

kind='kde',

hue='species',

height=3)

sns.displot(penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

hue="species",

col='island',

kind="kde",

height=3)

Plotting joint and marginal distributions

sns.jointplot(data=penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

hue='species',

height=4)

sns.jointplot(data=penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

kind='hist',

height=4)

sns.jointplot(data=penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

hue='species',

kind='kde',

height=4)

g = sns.jointplot(data=penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

height=4)

type(g)seaborn.axisgrid.JointGrid

jointplot() is an interface to the JointGrid class, which has helpful functions like plot_joint and plot_marginal.

g = sns.jointplot(data=penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

height=4)

g.plot_joint(sns.kdeplot,

color="red")

# scatter plot in blue

g = sns.jointplot(data=penguins,

x="bill_length_mm",

y="bill_depth_mm",

height=4)

# kde plot in red, same plot

g.plot_joint(sns.kdeplot,

color="red")

# rug plot in green

g.plot_marginals(sns.rugplot,

color="green", height=0.15)

Multiple variables

sns.pairplot(penguins, hue='species',

height=2.5)

Seaborn Catplot

catplot is similar to relplot, but designed specifically for categorical data.

Generally speaking, there are three different families of categorical plots in Seaborn:

Categorical scatterplots:

stripplot()(withkind="strip"; the default)swarmplot()(withkind="swarm")

Categorical distribution plots:

boxplot()(withkind="box")violinplot()(withkind="violin")

Categorical estimate plots:

pointplot()(withkind="point")barplot()(withkind="bar")countplot()(withkind="count")

Categorical scatterplots

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="tip",

# kind='strip' # default is 'strip'

jitter=False, # default is True

height=4.5)

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="tip",

kind="swarm",

height=4.5)/Users/gm845/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/seaborn/categorical.py:3399: UserWarning:

9.7% of the points cannot be placed; you may want to decrease the size of the markers or use stripplot.

/Users/gm845/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/seaborn/categorical.py:3399: UserWarning:

8.0% of the points cannot be placed; you may want to decrease the size of the markers or use stripplot.

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="tip",

hue="time",

kind="swarm",

height=4.5)/Users/gm845/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/seaborn/categorical.py:3399: UserWarning:

9.7% of the points cannot be placed; you may want to decrease the size of the markers or use stripplot.

/Users/gm845/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/seaborn/categorical.py:3399: UserWarning:

8.0% of the points cannot be placed; you may want to decrease the size of the markers or use stripplot.

/Users/gm845/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/seaborn/categorical.py:3399: UserWarning:

6.5% of the points cannot be placed; you may want to decrease the size of the markers or use stripplot.

We can use different color palettes:

https://seaborn.pydata.org/tutorial/color_palettes.html

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

hue="size",

col='sex',

palette=sns.color_palette("Blues"),

height=4)

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="day",

hue="time",

col='sex',

height=4)

Categorical distribution plots

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

kind="box",

height=4)

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

hue="smoker",

kind="box",

height=4)

sns.catplot(

data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

hue="sex",

kind='violin'

)

sns.catplot(

data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

hue="sex",

col='time',

kind="violin",

split=True,

)

sns.catplot(

data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

hue="sex",

kind="violin",

inner='stick',

split=True,

)

sns.catplot(

data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

col="sex",

kind="violin",

inner='stick',

split=True,

)

Categorical estimate plots

Barplots take the mean by default.

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

hue="sex",

# errorbar="ci" - default - uses bootstrapping to compute a confidence interval around the estimate

kind="bar",

height=3)

(tips.groupby(['sex', 'day']))['total_bill'].agg(['mean', 'std'])/var/folders/f0/m7l23y8s7p3_0x04b3td9nyjr2hyc8/T/ipykernel_4800/191020303.py:1: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| mean | std | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| sex | day | ||

| Male | Thur | 18.714667 | 8.019728 |

| Fri | 19.857000 | 10.015847 | |

| Sat | 20.802542 | 9.836306 | |

| Sun | 21.887241 | 9.129142 | |

| Female | Thur | 16.715312 | 7.759764 |

| Fri | 14.145556 | 4.788547 | |

| Sat | 19.680357 | 8.806470 | |

| Sun | 19.872222 | 7.837513 |

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="total_bill",

hue="sex",

kind="bar",

errorbar='sd',

height=3) # interval is +/- 1 sd around the estimate

Here are some more details about the kinds of error bars available in Seaborn.

sns.catplot(

data=tips,

x="day",

hue="sex",

kind="count", # no calculating mean, just count

height=4

)

sns.catplot(data=tips,

x="day",

y="tip",

hue="sex",

kind="point",

markers=['<', 'o'],

height=3,

aspect=1.5)

Let’s see if we can do something more informative.

tips['perc'] = tips['tip'] / tips['total_bill']

tips_subset = tips[['sex', 'day', 'perc']]

tips_mean = tips_subset.groupby('day')['perc'].mean()

tips_mean = pd.DataFrame(tips_mean)

tips_mean.columns = ['mean']

tips_subset = tips_subset.merge(tips_mean, on='day')

tips_subset['diff'] = tips_subset['perc'] - tips_subset['mean']/var/folders/f0/m7l23y8s7p3_0x04b3td9nyjr2hyc8/T/ipykernel_4800/3189921240.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

tips_subset| sex | day | perc | mean | diff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Female | Sun | 0.059447 | 0.166897 | -0.107451 |

| 1 | Male | Sun | 0.160542 | 0.166897 | -0.006356 |

| 2 | Male | Sun | 0.166587 | 0.166897 | -0.000310 |

| 3 | Male | Sun | 0.139780 | 0.166897 | -0.027117 |

| 4 | Female | Sun | 0.146808 | 0.166897 | -0.020090 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 239 | Male | Sat | 0.203927 | 0.153152 | 0.050775 |

| 240 | Female | Sat | 0.073584 | 0.153152 | -0.079568 |

| 241 | Male | Sat | 0.088222 | 0.153152 | -0.064929 |

| 242 | Male | Sat | 0.098204 | 0.153152 | -0.054947 |

| 243 | Female | Thur | 0.159744 | 0.161276 | -0.001531 |

244 rows × 5 columns

sns.catplot(tips_subset, x='day', y='diff', hue='sex', kind='box')

plt.axhline(y=0, color='darkgrey', linestyle='dotted', alpha=0.7)

Another categorical example

crashes = sns.load_dataset("car_crashes")

crashes = crashes.sort_values("total", ascending=False)crashes.head()| total | speeding | alcohol | not_distracted | no_previous | ins_premium | ins_losses | abbrev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 23.9 | 9.082 | 9.799 | 22.944 | 19.359 | 858.97 | 116.29 | SC |

| 34 | 23.9 | 5.497 | 10.038 | 23.661 | 20.554 | 688.75 | 109.72 | ND |

| 48 | 23.8 | 8.092 | 6.664 | 23.086 | 20.706 | 992.61 | 152.56 | WV |

| 3 | 22.4 | 4.032 | 5.824 | 21.056 | 21.280 | 827.34 | 142.39 | AR |

| 17 | 21.4 | 4.066 | 4.922 | 16.692 | 16.264 | 872.51 | 137.13 | KY |

sns.stripplot(crashes, x='total',

y='abbrev')

plt.gca().xaxis.grid(False)

plt.gca().yaxis.grid(True)

plt.gcf().set_size_inches(5, 10)

plt.gca().set(xlim=(0, 25), title='Total crashes', xlabel="", ylabel="")[(0.0, 25.0),

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Total crashes'),

Text(0.5, 0, ''),

Text(0, 0.5, '')]

Heatmaps

rates = pd.read_csv('../data/rates.csv')

rates.Time = pd.to_datetime(rates.Time)corr_mat = rates.corr(numeric_only=True)corr_mat| USD | JPY | BGN | CZK | DKK | GBP | CHF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USD | 1.000000 | -0.103337 | NaN | -0.218888 | -0.232007 | 0.074199 | -0.042449 |

| JPY | -0.103337 | 1.000000 | NaN | 0.655093 | 0.463510 | 0.484794 | 0.901636 |

| BGN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| CZK | -0.218888 | 0.655093 | NaN | 1.000000 | 0.008358 | 0.128065 | 0.649767 |

| DKK | -0.232007 | 0.463510 | NaN | 0.008358 | 1.000000 | 0.307508 | 0.604572 |

| GBP | 0.074199 | 0.484794 | NaN | 0.128065 | 0.307508 | 1.000000 | 0.424830 |

| CHF | -0.042449 | 0.901636 | NaN | 0.649767 | 0.604572 | 0.424830 | 1.000000 |

corr_mat = corr_mat.drop(index='BGN', columns='BGN')sns.heatmap(corr_mat)

For continuous scales, we can use the argument cmap (before, we used palette for discrete colors).

sns.heatmap(corr_mat, cmap='RdBu', center = 0)

sns.heatmap(corr_mat, cmap='RdBu_r', center = 0, annot=True)

Clustermap

# Load the brain networks example dataset

df = sns.load_dataset("brain_networks", header=[0, 1, 2], index_col=0)# Select a subset of the networks

used_networks = [1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 17]

used_columns = (df.columns.get_level_values("network")

.astype(int)

.isin(used_networks))

df = df.loc[:, used_columns]sns.heatmap(df.corr(), cmap='vlag', center = 0)

We can plot clusters using sns.clustermap, which plots a matrix dataset as a hierarchically-clustered heatmap.

Hierarchical clustering: 1. treats every data point as its own cluster 2. forms one cluster by combining the two closest clusters 3. repeat step 2. until there is one big cluster

sns.clustermap uses scipy for hierarchical clustering, details here.

# get color palette

network_pal = sns.husl_palette(len(used_networks), s=.45)

# return hues with constant lightness and saturation in the HUSL system.

# s: saturation intensity

network_lut = dict(zip(map(str, used_networks), network_pal))df.columns.get_level_values("network")Index(['1', '1', '5', '5', '6', '6', '6', '6', '7', '7', '7', '7', '7', '7',

'8', '8', '8', '8', '8', '8', '12', '12', '12', '12', '12', '13', '13',

'13', '13', '13', '13', '17', '17', '17', '17', '17', '17', '17'],

dtype='object', name='network')# Convert the palette to vectors that will be drawn on the side of the matrix

networks = df.columns.get_level_values("network")

network_colors = pd.Series(networks, index=df.columns).map(network_lut)g = sns.clustermap(df.corr(), center=0, cmap="vlag",

row_colors=network_colors, col_colors=network_colors,

row_cluster = False,

dendrogram_ratio=(.1, .2), # how much of plot should be dendrogram

cbar_pos=(.02, .32, .03, .2), # (left, bottom, width, height)

linewidths=.75, # space between squares

figsize=(12, 13))

Colors

Matplotlib master class

So far, we have used Seaborn functions, which are built on matplotlib.

Full customization of Seaborn plots requires some knowledge of matplotlib concepts.

We’ll start with some basic matplotlib functions.

data1_x = np.linspace(-4, 4, num=50)

data1_y1 = np.cos(data1_x)

data1_y2 = np.sin(data1_x)plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y1)

plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y2)

# plt.show # when matplotlib is used in a terminal or .py script, need this

https://matplotlib.org/stable/api/markers_api.html

plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y1, marker="X")

plt.scatter(data1_x, data1_y1)

plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y1)

- Call

plt.legend()to show labels - Call

plt.xlabel(my_label)to add a label to the x-axis - Call

plt.ylabel(my_label)to add a label to the y-axis - Call

plt.title(my_title)to add a title to the plot

plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y1, label='cosine')

plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y2, label='sine')

plt.legend()

Other useful things

plt.legend(loc="lower left", ncol=2): lower|center|upper + left|center|rightplt.xlim(left, right)plt.ylim(bottom, top)

plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y1, label='cosine')

plt.plot(data1_x, data1_y2, label='sine')

plt.legend(loc="lower right", ncol=2)

Details

When we call plt.plot(), Matplotlib implicitly creates:

- a Figure

- Axes

A Figure is a top-level container that can hold one or more plots. It is like the blank canvas for your plots. It can contain: multiple subplots, colorbars, legends, titles.

An Axes is the plot where the data is displayed, containing the data points, tick marks, grid lines.

To have more control over our plots, we can specify the Figure and Axes directly.

# create a figure object: the container of the plot, and with an axis on it

figure, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(data1_x, data1_y1)

ax.plot(data1_x, data1_y2)

Anatomy of a matplotlib figure

Credits: https://matplotlib.org/stable/gallery/showcase/anatomy.html#anatomy-of-a-figure

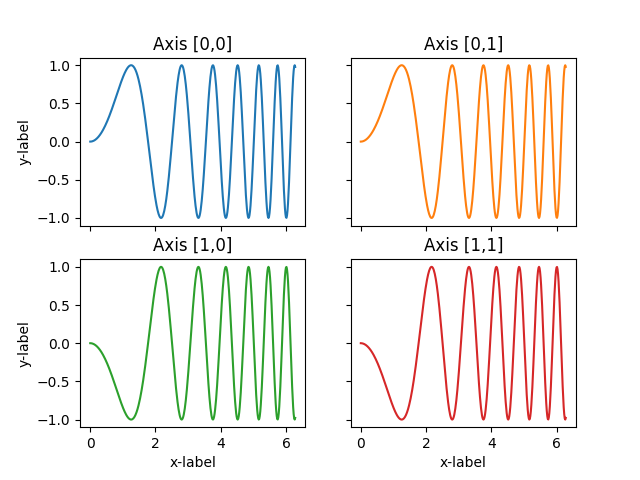

Subplots

Credits: https://matplotlib.org/3.1.0/gallery/subplots_axes_and_figures/subplots_demo.html

figure, axes = plt.subplots(

nrows=2, ncols=2,

figsize=(7,4),

gridspec_kw={'width_ratios': [1, 2]} # specifies width ratios

)

axes[0,0].plot(data1_x, data1_y1, label='cosine')

axes[1,0].plot(data1_x, data1_y2, label='sine')

axes[0,0].legend()

axes[1,0].legend()

# all the plt.xlabel become ax.set_xlabel ...

axes[0,0].set_xlabel("x")

axes[1,0].set_xlabel("x")

axes[0,0].set_ylabel("y")

axes[1,0].set_ylabel("$y_1$")

axes[0,0].set_title("Cosine Plot")

axes[1,0].set_title("Sine Plot")

axes[0,1].hist(np.random.normal(size=(500)))

axes[1,1].hist(np.random.beta(0.5, 0.5, size=(500)))

axes[0,1].set_ylabel('Density')

figure.suptitle("The suptitle") # suptitle stands for "super-title" - it describes ALL plots in a figure.

# This automatically adjusts padding to fit plots in figure without overlap

figure.tight_layout()

figure, axes = plt.subplots(

nrows=1, ncols=2,

figsize=(5.5,2)

)

axes[0].plot(data1_x, data1_y1, linestyle=(0, (3, 5, 1, 5)), color='green')

axes[1].plot(data1_x, data1_y2)

extra_ax = figure.add_axes((0.7, 0.7, 0.2,0.2)) # coordinates from bottom left, then size

extra_ax.plot(data1_x, data1_y1)

See more linestyles here.

Subplot Mosaic:

plt.subplot_mosaic takes two lists, each list representing a row, and each element in the list a key representing the column.

(Adapted from https://matplotlib.org/stable/users/explain/axes/arranging_axes.html#basic-2x2-grid)

fig, axd = plt.subplot_mosaic([['upper left', 'right'],

['lower left', 'right']],

figsize=(5.5, 3.5), layout="constrained")

for k, ax in axd.items():

ax.text(0.5, 0.5,

f'axd[{k!r}]', # !r adds quotations

ha="center", va="center",

fontsize=14, color="darkgrey")

fig.suptitle('plt.subplot_mosaic()')Text(0.5, 0.98, 'plt.subplot_mosaic()')

fig, axd = plt.subplot_mosaic([['upper left', 'right'],

['lower left', 'right']],

figsize=(6, 4), layout="constrained")

rates.USD.plot(ax=axd['upper left'])

rates.USD.hist(ax=axd['right'])

rates.reset_index().plot.scatter(x='index', y='USD', ax=axd['lower left'])

Adding multiple lines

Example from https://wesmckinney.com/book/plotting-and-visualization

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 4))

ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", label="one")

ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", linestyle="dashed",label="two")

ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", linestyle="dotted",label="three")

ax.legend()

Adding text

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 3))

ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", label="one")

ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", linestyle="dashed",label="two")

ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", linestyle="dotted",label="three")

ax.legend()

ax.text(500, 0, "Hello world!",

family="monospace", fontsize=10)Text(500, 0, 'Hello world!')

Back to mpg data:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

ax.scatter(mpg.displ, mpg.hwy)

ax.set_xlabel('Engine Displacement (L)')

ax.set_ylabel('Highway miles per gallon')Text(0, 0.5, 'Highway miles per gallon')

outliers = (mpg.hwy > 40) | ((mpg.displ > 5) & (mpg.hwy > 20))

inliers = ~outliersinds = np.where(outliers)[0]indsarray([ 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 158, 212, 221, 222])col = pd.Series(['#1f77b4', '#ff7f0e']).take(outliers)fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

ax.scatter(mpg.displ, mpg.hwy, c=col)

ax.set_xlabel('Engine Displacement (L)')

ax.set_ylabel('Highway miles per gallon')

for i in inds:

ax.annotate(text= mpg.model[i],

xy = (mpg.displ[i], mpg.hwy[i]),

xytext = (mpg.displ[i] + 0.2, mpg.hwy[i]))

Plotting datetime and adding annotations

from datetime import datetime

data = pd.read_csv("../data/spx.csv", index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

spx = data["SPX"]spx.asof(datetime(2008, 1, 1))np.float64(1468.36)fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,4))

spx.plot(ax=ax, color="black")

crisis_data = [

(datetime(2007, 10, 11), "Peak of bull market"),

(datetime(2008, 3, 12), "Bear Stearns Fails"),

(datetime(2008, 9, 15), "Lehman Bankruptcy")

]

for date, label in crisis_data:

ax.annotate(label, # Text to display

xy=(date, spx.asof(date) + 75), # Point to annotate (arrow points here)

xytext=(date, spx.asof(date) + 225), # Text position

arrowprops=dict(facecolor="black", headwidth=4, width=2,headlength=4), # Arrow properties

horizontalalignment="left", verticalalignment="top",

)

# Zoom in on 2007-2010

ax.set_xlim(["1/1/2007", "1/1/2011"])

ax.set_ylim([600, 1800])

ax.set_title("Important dates in the 2008–2009 financial crisis")Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Important dates in the 2008–2009 financial crisis')

Matplotlib configuration

Matplotlib comes configured with color schemes and defaults.

The default behavior can be customized via global parameters governing figure size, subplot spacing, colors, font sizes, grid styles, etc.

All of the current configuration settings are found in the plt.rcParams dictionary, and they can be restored to their default values by calling the plt.rcdefaults() function.

plt.rcdefaults()

plt.rcParams['figure.dpi']100.0plt.rc("figure", dpi=120)# see what rcParams changes to

plt.rcParams['figure.dpi']120.0To modify configurations, there are a few options:

- use

plt.rcto changeplt.rcParamsdirectly: useful if we want to affect all plots - create a figure with a specific dpi/size:

fig = plt.figure(dpi=120, figsize=[10, 12]): useful for a single plot - use a context manager

with plt.rc_context({"figure.dpi": 120}): useful for a series of plots

list(plt.rcParams.keys())[0:5]['_internal.classic_mode',

'agg.path.chunksize',

'animation.bitrate',

'animation.codec',

'animation.convert_args']import matplotlib.dates as mdates

import matplotlib

with plt.rc_context(

{"figure.figsize": [15, 3],

"figure.dpi": 110,

"axes.labelsize": 15}), plt.style.context("dark_background"):

plt.plot(rates['Time'], rates['USD'], color='red')

plt.ylabel("USD exchange rate")

plt.xlabel("date")

ax = plt.gca() # this gets current axes

my_fmt = mdates.DateFormatter("%d-%m-%Y")

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(my_fmt)

xlocator = mdates.DayLocator(interval=5) # major ticks every 5 days

ax.xaxis.set_major_locator(xlocator)

ax.minorticks_on()

ax.xaxis.set_minor_locator(matplotlib.ticker.AutoMinorLocator(5))

# plt.xticks affects current active plot

plt.xticks(rotation=45, ha="right", rotation_mode="anchor") # anchor: aligns the unrotated text and then rotates the text around the point of alignment.

# configure grid lines

plt.grid(axis="x", alpha=0.5)

plt.grid(axis="y", which="major", linewidth=0.5, linestyle="-", alpha=0.5)

Saving figures

From Data Science: A First Introduction with Python (Timbers et al. 2022):

Generally speaking, images come in two flavors: raster formats and vector formats.

Raster images:

- 2D grid of square pixels, each with its own color. Can be lossy or lossless.

- A format is lossy if the image cannot be perfectly re-created when loading. A format is lossless if it can re-create the original image exactly.

- Common file types:

- JPEG (.jpg, .jpeg): lossy, usually used for photographs

- PNG (.png): lossless, usually used for plots / line drawings

- BMP (.bmp): lossless, raw image data, no compression (rarely used)

- TIFF (.tif, .tiff): typically lossless, no compression, used mostly in graphic arts, publishing

Vector images:

- represented as a collection of mathematical objects (lines, surfaces, shapes, curves). When the computer displays the image, it redraws all of the elements using their mathematical formulas.

- Common file types:

- SVG (.svg): general-purpose use

- EPS (.eps), general-purpose use (rarely used)

Note: The portable document format PDF (.pdf) is commonly used to store both raster and vector formats. If you try to open a PDF and it’s taking a long time to load, it may be because there is a complicated vector graphics image that your computer is rendering.

Pros and cons

- Time to load

Raster images of fixed width/height take the same amount of space and time to load; a vector image takes space and time to load depending on how complex the image is.

- Pixelation

Raster images can look pixelated if you zoom in; vector images can be zoomed into without loss of image quality.

Fig. 4.30 from Data Science: A First Introduction with Python

Things to think about

- adjust the size of your figure based on your output goal; you don’t want points to look too small on presentation slides, for example

- adjust your text size to be readable based on your output goal (e.g. presentations require larger text than papers)

with plt.rc_context({'font.size': 10}):

sns.relplot(data=tips,

x="total_bill",

y="tip",

hue="sex",

aspect=1.5,

height=10)

# change font.size and height to see output

plt.savefig('../fig/tips.png', dpi=300)

plt.savefig('../fig/tips.pdf')

plt.savefig('../fig/tips.svg')--------------------------------------------------------------------------- FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[123], line 11 2 sns.relplot(data=tips, 3 x="total_bill", 4 y="tip", 5 hue="sex", 6 aspect=1.5, 7 height=10) 9 # change font.size and height to see output ---> 11 plt.savefig('../fig/tips.png', dpi=300) 12 plt.savefig('../fig/tips.pdf') 13 plt.savefig('../fig/tips.svg') File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/matplotlib/pyplot.py:1243, in savefig(*args, **kwargs) 1240 fig = gcf() 1241 # savefig default implementation has no return, so mypy is unhappy 1242 # presumably this is here because subclasses can return? -> 1243 res = fig.savefig(*args, **kwargs) # type: ignore[func-returns-value] 1244 fig.canvas.draw_idle() # Need this if 'transparent=True', to reset colors. 1245 return res File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/matplotlib/figure.py:3490, in Figure.savefig(self, fname, transparent, **kwargs) 3488 for ax in self.axes: 3489 _recursively_make_axes_transparent(stack, ax) -> 3490 self.canvas.print_figure(fname, **kwargs) File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/matplotlib/backend_bases.py:2184, in FigureCanvasBase.print_figure(self, filename, dpi, facecolor, edgecolor, orientation, format, bbox_inches, pad_inches, bbox_extra_artists, backend, **kwargs) 2180 try: 2181 # _get_renderer may change the figure dpi (as vector formats 2182 # force the figure dpi to 72), so we need to set it again here. 2183 with cbook._setattr_cm(self.figure, dpi=dpi): -> 2184 result = print_method( 2185 filename, 2186 facecolor=facecolor, 2187 edgecolor=edgecolor, 2188 orientation=orientation, 2189 bbox_inches_restore=_bbox_inches_restore, 2190 **kwargs) 2191 finally: 2192 if bbox_inches and restore_bbox: File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/matplotlib/backend_bases.py:2040, in FigureCanvasBase._switch_canvas_and_return_print_method.<locals>.<lambda>(*args, **kwargs) 2036 optional_kws = { # Passed by print_figure for other renderers. 2037 "dpi", "facecolor", "edgecolor", "orientation", 2038 "bbox_inches_restore"} 2039 skip = optional_kws - {*inspect.signature(meth).parameters} -> 2040 print_method = functools.wraps(meth)(lambda *args, **kwargs: meth( 2041 *args, **{k: v for k, v in kwargs.items() if k not in skip})) 2042 else: # Let third-parties do as they see fit. 2043 print_method = meth File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/matplotlib/backends/backend_agg.py:481, in FigureCanvasAgg.print_png(self, filename_or_obj, metadata, pil_kwargs) 434 def print_png(self, filename_or_obj, *, metadata=None, pil_kwargs=None): 435 """ 436 Write the figure to a PNG file. 437 (...) 479 *metadata*, including the default 'Software' key. 480 """ --> 481 self._print_pil(filename_or_obj, "png", pil_kwargs, metadata) File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/matplotlib/backends/backend_agg.py:430, in FigureCanvasAgg._print_pil(self, filename_or_obj, fmt, pil_kwargs, metadata) 425 """ 426 Draw the canvas, then save it using `.image.imsave` (to which 427 *pil_kwargs* and *metadata* are forwarded). 428 """ 429 FigureCanvasAgg.draw(self) --> 430 mpl.image.imsave( 431 filename_or_obj, self.buffer_rgba(), format=fmt, origin="upper", 432 dpi=self.figure.dpi, metadata=metadata, pil_kwargs=pil_kwargs) File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/matplotlib/image.py:1634, in imsave(fname, arr, vmin, vmax, cmap, format, origin, dpi, metadata, pil_kwargs) 1632 pil_kwargs.setdefault("format", format) 1633 pil_kwargs.setdefault("dpi", (dpi, dpi)) -> 1634 image.save(fname, **pil_kwargs) File ~/anaconda3/envs/msds597/lib/python3.12/site-packages/PIL/Image.py:2591, in Image.save(self, fp, format, **params) 2589 fp = builtins.open(filename, "r+b") 2590 else: -> 2591 fp = builtins.open(filename, "w+b") 2592 else: 2593 fp = cast(IO[bytes], fp) FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: '../fig/tips.png'

Resources

Here are some helpful examples:

Visualization more broadly:

A good textbook: - Fundamentals of Data Visualization, Wilke